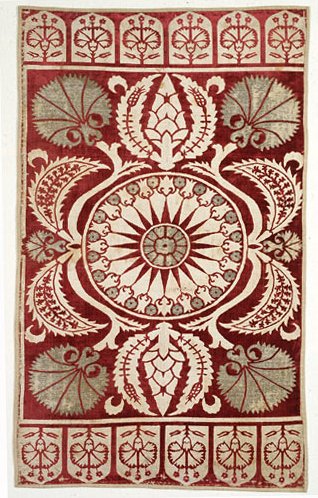

17th-century Ottoman velvet cushion cover, with stylized carnation motifs.

Floral motifs were common in Ottoman art.The origin of carpet weaving remains unknown, as carpets are subject to use, wear, and destruction by insects and rodents. Controversy arose over the accuracy of the claim[2] that the oldest records of flat woven kilims come from the Çatalhöyük excavations, dated to circa 7000 BC.[3] The excavators' report[4] remained unconfirmed, as it states that the wall paintings depicting kilim motifs had disintegrated shortly after their exposure.The history of rug weaving in Anatolia must be understood in the context of the country's political and social history. Anatolia was home to ancient civilizations, such as the Hittites, the Phrygians, the Assyrians, the Ancient Persians, the Armenians, the Ancient Greeks, and the Byzantine Empire. Rug weaving is assumed to already exist in Anatolia during this time, however there are no examples of pre-Turkic migration rugs in Anatolia. In 1071 AD, the Seljuq Alp Arslan defeated the Roman Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at Manzikert. This is regarded as the beginning of the ascendancy of the Seljuq Turks.Seljuq rugs: Travelers' reports and the Konya fragmentseditIn the early fourteenth century, Marco Polowrote in the account of his travels:...In Turcomania there are three classes of people. First, there are the Turcomans; these are worshippers of Mahommet, a rude people with an uncouth language of their own. They dwell among mountains and downs where they find good pasture, for their occupation is cattle-keeping. Excellent horses, known as Turquans, are reared in their country, and also very valuable mules. The other two classes are the Armenians and the Greeks, who live mixt with the former in the towns and villages, occupying themselves with trade and handicrafts. They weave the finest and handsomest carpets in the world, and also a great quantity of fine and rich silks of cramoisy and other colours, and plenty of other stuffs.[5]Coming from Persia, Polo travelled from Sivas to Kayseri. Abu'l-Fida, citing Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi refers to rug export from Anatolian cities in the late 13th century: "That's where Turkoman carpets are made, which are exported to all other countries". He and the Moroccan merchant Ibn Battuta mention Aksaray as a major rug weaving center in the early-to-mid-14th century.The earliest surviving woven rugs were found in Konya, Beyşehir and Fostat, and were dated to the 13th century. These carpets from the Anatolian Seljuq Period (1243–1302) are regarded as the first group of Anatolian rugs. Eight fragments were found in 1905 by F.R. Martin[6] in the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya, four in the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir in Konya province by R.M. Riefstahl in 1925.[7] More fragments were found in Fostat, today a suburb of the city of Cairo.[8]Judging by their original size (Riefstahl reports a carpet up to 6 m long), the Konya carpets must have been produced in town manufactories, as looms of this size can hardly have been set up in a nomadic or village home. Where exactly these carpets were woven is unknown. The field patterns of the Konya rugs are mostly geometric, and small in relation to the carpet size. Similar patterns are arranged in diagonal rows: Hexagons with plain, or hooked outlines; squares filled with stars, with interposed kufic-like ornaments; hexagons in diamonds composed of rhomboids filled with stylized flowers and leaves. Their main borders often contain kufic ornaments. The corners are not "resolved", which means that the border design is cut off, and does not continue diagonally around the corners. The colours (blue, red, green, to a lesser extent also white, brown, yellow) are subdued, frequently two shades of the same colour are opposed to each other. Nearly all carpet fragments show different patterns and ornaments.The Beyşehir rugs are closely related to the Konya specimen in design and colour.[9] In contrast to the "animal carpets" of the following period, depictions of animals are rarely seen in the Seljuq fragments. Rows of horned quadrupeds placed opposite to each other, or birds beside a tree can be recognized on some fragments.The style of the Seljuq rugs has parallels amongst the architectural decoration of contemporaneous mosques such as those at Divriği, Sivas, and Erzurum, and may be related to Byzantine art.[10] Today, the rugs are kept at the Mevlana Museum in Konya, and at the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul.

Seljuq rugs: Travelers' reports and the Konya fragments

•

Seljuq carpet, 320 x 240 cm, from Alaeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century[11]

•

Rug fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

•

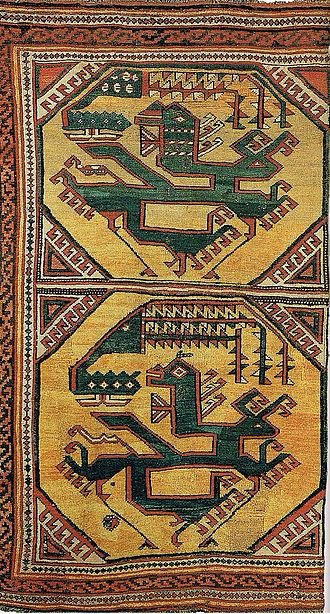

Animal carpet, dated to the 11th–13th century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Rugs of the Anatolian Beyliks

Early in the thirteenth century, the territory of Anatolia was invaded by Mongols. The weakening of Seljuq rule allowed Turkmen tribes known as the Oghuz Turks to organize themselves into independent sovereignties, the Beyliks. These were later integrated into the Ottoman Empire by the sultans Bayezid I(1389-1402), Murad II (1421-1481), Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481), and Selim I (1512-1520).Literary sources like the Book of Dede Korkutconfirm that the Turkoman tribes produced carpets in Anatolia. What types of carpets were woven by the Turkoman Beyliks remains unknown, since we are unable to identify them. One of the Turkoman tribes of the Beylik group, the Tekke settled in South-western Anatolia in the eleventh century, and moved back to the Caspian sea later. The Tekke tribes of Turkmenistan, living around Merv and the Amu Darya during the 19th century and earlier, wove a distinct type of carpet characterized by stylized floral motifs called guls in repeating rows.Ottoman carpetseditAround 1300 AD, a group of Turkmen tribes under Suleiman and Ertugrul moved westward. Under Osman I, they founded the Ottoman Empire in northwestern Anatolia; in 1326, the Ottomans conquered Bursa, which became the first capital of the Ottoman state. By the late 15th century, the Ottoman state had become a major power. In 1517, the Egyptian Sultanate of the Mamluks was overthrown in the Ottoman–Mamluk war.Suleiman the Magnificent, the tenth Sultan(1520-1566), invaded Persia and forced the Persian Shah Tahmasp (1524–1576) to move his capital from Tabriz to Qazvin, until the Peace of Amasya was agreed upon in 1555.As the political and economical influence grew of the Ottoman Empire, Istanbul became a meeting point of diplomats, merchants and artists. During Suleiman I.'s reign, artists and artisans of different specialities worked together in court manufactures (Ehl-i Hiref). Calligraphy and miniature painting were performed in the calligraphy workshops, or nakkaşhane, and influenced carpet weaving. Besides Istanbul, Bursa, Iznik, Kütahya and Ushak were homes to manufactories of different specializations. Bursa became known for its silk cloths and brocades, Iznik and Kütahya were famous for ceramics and tiles, Uşak, Gördes, and Ladik for their carpets. The Ushak region, one of the centers of Ottoman "court" production, Holbein and Lotto carpetswere woven here. Gold-brocaded silk velvet carpets known as Çatma are associated with the old Ottoman capital of Bursa, in Western Anatolia near the Sea of Marmara.

15th century "animal" rugs

Early Anatolian Animal carpets

See also: Early Anatolian Animal carpets

FIRST image: Phoenix and Dragon carpet, 164 x 91 cm, Anatolia, circa 1500, Pergamon Museum, Berlin SECOUND image: Animal carpet, around 1500, found in Marby Church, Jämtland, Sweden. Wool, 160 cm x 112 cm, Swedish History Museum, Stockholm Very few carpets still exist today which represent the transition between the late Seljuq and early Ottoman period. A traditional Chinese motif, the fight between phoenix and dragon, is seen in an Anatolian rug today at the Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the "Dragon and Phoenix" carpet was woven in the mid 15th century, during the early Ottoman Empire. It is knotted with symmetric knots. The Chinese motif was probably introduced into Islamic art by the Mongols during the thirteenth century.[13] Another carpet showing two medallions with two birds besides a tree was found in the Swedish church of Marby. More fragments were found in Fostat, today a suburb of the city of Cairo.A carpet with serial bird-and-tree medallions is shown in Sano di Pietro's painting "Marriage of the Virgin" (1448–52).The "Dragon and Phoenix" and the "Marby" rugs were the only existing examples of Anatolian animal carpets known until 1988. Since then, seven more carpets of this type have been found. They survived in Tibetan monasteries and were removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the Chinese cultural revolution. One of these carpets was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[14] which parallels a painting by the Sienese artist Gregorio di Cecco: "The Marriage of the Virgin", 1423.It shows large confronted animals, each with a smaller animal inside.More animal carpets were depicted in Italian paintings of the 14th and 15th century, and thus represent the earliest Oriental carpets shown in Renaissance paintings. Although only few examples for early Anatolian carpets have survived, European paintings inform the knowledge about late Seljuk and early Ottoman carpets. By the end of the 15th century, geometrical ornaments became more frequent.Holbein and Lotto carpetseditBased on the distribution and size of their geometric medallions, a distinction is made between "large" and "small" Holbein carpets. The small Holbein type is characterized by small octagons, frequently including a star, which are distributed over the field in a regular pattern, surrounded by arabesques. The large Holbein type show two or three large medallions, often including eight-pointed stars. Their field is often covered in minute floral ornaments. These "Ushak" carpets can be found in places such as the MAK in Vienna, the Louvre in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Lotto carpets show a yellow grid of geometric arabesques, with interchanging cruciform, octagonal, or diamond shaped elements. The oldest examples have "kufic" borders. The field is always red, and is covered with bright yellow leaves on an underlying rapport of octagonal or rhombiform elements. Carpets of various sizes up to 6 meters square are known. Ellis distinguishes three principal design groups for Lotto carpets: the Anatolian-style, kilim-style, and ornamental style.[16]Holbein and Lotto carpets have little in common with decorations and ornaments seen on Ottoman art objects other than carpets.Briggs demonstrated similarities between both types of carpets, and Timurid carpets depicted in miniature paintings. The Holbein and Lotto carpets may represent a design tradition dating back to the Timurid period.

• Type I small-pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia, 16th century.

• The Harem Room, Topkapi Palace, carpet with a small-pattern "Holbein" design

• Type IV large-pattern Holbein carpet, 16th century, Central Anatolia.

Western Anatolian ‘Lotto’-rug, 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum

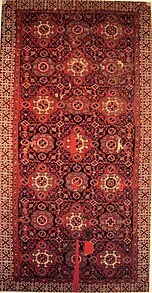

Ushak carpets were woven in large formats. They are characterized by large dark blue star shaped primary medallions in infinite repeat on a red ground field containing a secondary floral scroll. The design was likely influenced by northwest Persian book design, or by Persian carpet medallions.[19] As compared to the medallion Ushak carpets, the concept of the infinite repeat in star Ushak carpets is more accentuated and in keeping with the early Turkish design tradition.[20]Because of their strong allusion to the infinite repeat, the star Ushak design can be used on carpets of various size and in many varying dimensions.

Fragment of a Medallion Ushak carpet, ca. 1600. Museum of Islamic Art, BerlinMedallion Ushak carpets usually have a red or blue field decorated with a floral trellis or leaf tendrils, ovoid primary medallions alternating with smaller eight-lobed stars, or lobed medallions, intertwined with floral tracery. Their border frequently contains palmettes on a floral and leaf scroll, and pseudo-kufic characters.[21]Medallion Ushak carpets with their curvilinear patterns significantly depart from the designs of earlier Turkish carpets. Their emergence in the sixteenth century hints at a potential impact of Persian designs. Since the Ottoman Turks occupied the former Persian capital of Tabriz in the first half of the sixteenth century, they would have knowledge of, and access to Persian medallion carpets. Several examples are known to have been in Turkey at an early date, such as the carpet that Erdmann found in the Topkapı Palace.[22] The Ushak carpet medallion, however, conceived as part of an endless repeat, represents a specific Turkish idea, and is different from the Persian understanding of a self-contained central medallion.[23]Star and medallion Ushaks represent an important innovation, as in them, floral ornaments appear in Turkish carpets for the first time. The replacement of floral and foliate ornaments by geometrical designs, and the substitution of the infinite repeat by large, centered compositions of ornaments, was termed by Kurt Erdmann the "pattern revolution".[24]Another small group of Ushak carpets is called Double-niche Ushaks. In their design, the corner medallions have been moved closely together, so that they form a niche on both ends of the carpet. This has been understood as a prayer rug design, because a pendant resembling a mosque lamp is suspended from one of the niches. The resulting design scheme resembles the classical Persian medallion design. Counterintuitive to the prayer rug design, some of the double niche Ushaks have central medallions as well. Double niche Ushaks thus may provide an example for the integration of Persian patterns into an older Anatolian design tradition.[9][25]White ground (Selendi) rugs

White-ground "Selendi" rug with bird-like ornaments. Monastery Church of Sighișoara, Romania.Examples are also known of rugs woven in the Ushak area whose fields are covered by ornaments like the Cintamani motif, made of three coloured orbs arranged in triangles, often with two wavy bands positioned under each triangle. This motiv usually appears on a white ground. Together with the bird and a very small group of so-called scorpion rugs, they form a group of known as "white ground rugs". Bird rugs have an allover geometrical field design of repeating quatrefoils enclosing a rosette. Although geometric in design, the pattern has similarities to birds. The rugs of the white ground group have been attributed to the nearby town of Selendi, based on an Ottoman official price list (narh defter) of 1640 which mentions a "white carpet with leopard design".[26]Ottoman Cairene rugseditAfter the 1517 Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt, two different cultures merged. The earlier tradition of the Mamluk carpet used "S" (clockwise) spun and "Z" (anti-clockwise)-plied wool, and a limited palette of colours and shades. After the conquest, the Cairene weavers adopted an Ottoman Turkish design.[27] The production of these carpets continued in Egypt, and probably also in Anatolia, into the early 17th century.[28]"Transylvanian" rugseditMain article: Transylvanian rugsTransylvania, in present-day Romania was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1526-1699. It was an important center for the carpet trade with Europe. Carpets were also valued in Transylvania, and Turkish carpets were used as decorative wall furnishings in Christian Protestant churches. Amongst others, the Brașov Black Church still shelters a variety of Anatolian carpets, called by convenience "Transylvanian carpets".[29] By their preservation in Christian churches, unusual as the setting may be, the carpets were protected from wear and the changes of history, and often remained in excellent condition. Amongst these carpets are well-preserved Holbein, Lotto, and Bird Ushak carpets.[30]The carpets termed "Transsylvanian carpets" by convenience today are of Ottoman origin, and were woven in Anatolia.[30][31] Usually their format is small, with borders of oblong, angular cartouches whose centers are filled with stylized, counterchanging vegetal motifs, sometimes interspersed with shorter stellated rosettes or cartouches. Their field often has a prayer niche design, with two pairs of vases with flowering branches symmetrically arranged towards the horizontal axis. In other examples, the field decor is condensed into medallions of concentric lozenges and rows of flowers. The spandrels of the prayer niche contain stiff arabesques or geometrical rosettes and leaves. The ground colour is yellow, red, or dark blue. The Transylvanian church records, as well as Netherlandish paintings from the seventeenth century which depict in detail carpets with this design, allow for precise dating.[32][33]

Left image: Pieter de Hooch: Portrait of a family making music, 1663, Cleveland Museum of ArtRight image: "Transylvanian" type prayer rug, 17th century, National Museum, WarsawBy the time "Transylvanian" carpets appear in Western paintings for the first time, royal and aristocratic subjects had mostly progressed to sit for portraits which depict Persian carpets.[34] Less wealthy sitters are still shown with the Turkish types: The 1620 Portrait of Abraham Grapheus by Cornelis de Vos, and Thomas de Keyser's "Portrait of an unknown man" (1626) and "Portrait of Constantijn Huyghens and his clerk" (1627) are amongst the earliest paintings depicting the "Transylvanian" types of Ottoman Turkish manufactory carpets. Transylvanian vigesimal accounts, customs bills, and other archived documents provide evidence that these carpets were exported to Europe in large quantities. Probably the increase in production reflects the increasing demand by an upper middle class who now could afford to buy these carpets.[35] Pieter de Hoochs 1663 painting "Portrait of a family making music" depicts an Ottoman prayer rug of the "Transylvanian" type.[35]Anatolian carpets of the "Transylvanian" type were also kept in other European churches in Hungary, Poland, Italy and Germany, whence they were sold, and reached European and American museums and private collections. Aside from the Transylvanian churches, the Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Romania,[36] the Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Skokloster Castle near Stockholm in Sweden keep important collections of "Transylvanian" carpets.Carpets are rarely found in Anatolia itself from the transitional period between the classical Ottoman era and the nineteenth century. The reason for this remains unclear. Carpets which can be reliably dated to the eighteenth century are of a small format. At the same time, western European residences were more sparely equipped with Oriental carpets. It seems likely that carpets were not exported in large scale during this time.[37]

Dolmabahçe Palace, Pink Hall, with typical "mecidi"-style carpetBy the end of the eighteenth century, the "turkish baroque" or "mecidi" style developed out of French baroque designs. Carpets were woven after the patterns of French Savonnerieand Aubusson tapestry. Sultan Abdülmecid I(1839–1861) built the Dolmabahçe Palace, modelled after the Palace of Versailles.A weaving workshop was established in 1843 in Hereke that supplied the royal palaces with silk brocades and other textiles. The Hereke Imperial Factory included looms that produced cotton fabric, in 1850 the cotton looms were moved to a factory in Bakirkoy, west of Istanbul, being replaced by Jacquard looms. Within its early years of production, it had only produced textiles exclusively for the Ottoman palaces, and in 1878, a fire had caused extensive damage and had closed production until 1882. Carpet production had begun in Hereke in 1891 and became a center for expert carpet weavers.Hereke carpets are known primarily for their fine weave. Silk thread or fine wool yarn and occasionally gold, silver and cotton thread are used in their production. Wool carpets produced for the palace had 60–65 knots per square centimeter, while silk carpets had 80–100 knots.[38]The oldest Hereke carpets, now exhibited in Topkapı and other palaces in Istanbul, contain a wide variety of colours and designs. The typical "palace carpet" features intricate floral designs, including the tulip, daisy, carnation, crocus, rose, lilac, and hyacinth. It often has quarter medallions in the corners. The medallion designs of earlier Ushak carpets was widely used at the Hereke factory. These medallions are curved on the horizontal axis and taper to points on the vertical axis. Hereke prayer rugs feature patterns of geometric motifs, tendrils and lamps as background designs within the representation of a mihrab(prayer niche). Once referring solely to carpets woven at Hereke, the term "Hereke carpet" now refers to any high quality carpet woven using similar techniques.

Modern history: Decline and revival

Left image: Pile rug, circa 1875; Southwestern Anatolia, with bright but harmonic natural dyesRight image: Tribal Kurdish Cuval, ca. 1880 in traditional design, with harsh synthetic colours.The modern history of carpets and rugs began in the nineteenth century when increasing demand for handmade carpets arose on the international market. However, the traditional, hand-woven, naturally dyed Turkish carpet is a very labour-intense product, as each step in its manufacture requires considerable time, from the preparation, spinning, dyeing of the wool to setting up the loom, knotting each knot by hand, and finishing the carpet before it goes to market. In an attempt to save on resources and cost, and maximise on profit in a competitive market environment, synthetic dyes, non-traditional weaving tools like the power loom, and standardized designs were introduced. This led to a rapid breakdown of the tradition, resulting in the degeneration of an art which had been cultivated for centuries. The process was recognized by art historians as early as in 1902.[39] It is hitherto unknown when exactly this process of degeneration started, but it is observed mainly since the large-scale introduction of synthetic colours took place.[40]In the late twentieth century, the loss of cultural heritage was recognized, and efforts started to revive the tradition. Initiatives were started aiming at re-establishing the ancient tradition of carpet weaving from handspun, naturally dyed wool.[41] The return to traditional dyeing and weaving by the producers, and the renewed customer interest in these carpets was termed by Eilland as the "Carpet Renaissance".[42]